The Moment of Painting / Helia Darabi

According to the Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder, two prominent contemporary painters stage a contest to determine the greater artist. Each of them makes an extremely realistic painting to win the contest. The story shows us the significance of representational skill and technical accomplishment in the evaluation of the medium. Such criterion dominated the Western artistic scene for centuries, and was always exalted in other cultures. In our age, however, art has left technical perfection far behind.

This process began when artists like Marcel Duchamp dismissed the necessity of craftsmanship in making art, and now painting and sculpture are considered “traditional media”. Painters who insist on painterly process seem to belong to another era and sculpture no longer sounds the suitable word for the objects artists make.

This is not to say that technical perfection is absent from the contemporary artworld. It seems to have been moved to other areas. Today, the scope of intellectual concerns of an artist –which makes up the building blocks of their works– are far wider than before. Also, it is no longer possible –or desirable– to put people in their early teens to apprenticeship with a great artist, for a lifetime, to achieve such degree of skillfulness.

But is painting still alive? If the main intention is to grasp the zeitgeist, is it still attainable through this medium? In fact, although the death of painting continues to be championed by such art critics as Douglas Crimp and Yve-Alain Bois, still the greatest and most influential contemporary artists are among painters who still deal with the effects of handling colored pigment and the magic of painterly expression.

Iranian Contemporary art has been witnessed a significant orientation toward new artistic media such as installations, video art, performance art and fine art photography during past two decades. However, painting has continued to thrive, being developed in terms of technical devices, subject matter, and interaction with other means and media. Soudeh Davoud is among the new generation of Iranian artists to find painting the most suitable media to express her issues and concerns, and by focusing on the inherent potentials of painting, she has reached an exceptional level of practical accomplishment among her generation of artists. Her painterly expression combines the expressive means and potentials of figurative as well as abstract painting.

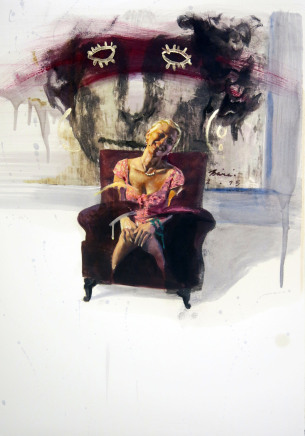

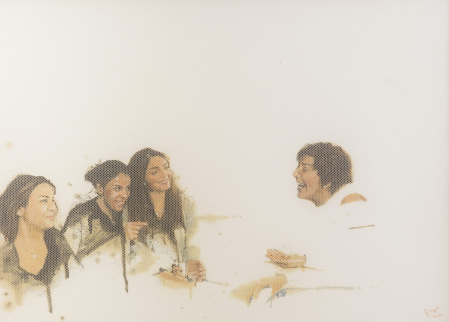

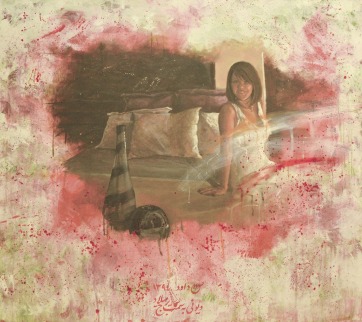

Human figures are the main protagonists of Davoud’s new series. The main scene –consisting of a momentary interaction between the figures and basically taken from a photograph- has been organized in the middle of the canvas, amidst an abstract background full of expressive touches and patterns. The background has been largely left blank in the smaller paintings. Parts of the bodies are always left untouched, making the figures feel like ghostly beings merged into the background. The artist’s skillfulness in design, paint handling, space definition and merging figurative and abstract spheres is commendable.

Also, she demonstrates a powerful combination of painting and drawing, and the ambiance each medium can make. A layer of net textile is drawn upon all paintings, disturbing a whole sight of the image, and making the viewer keep changing the position of their head to better view the picture. It demands a bodily ritual before each canvas. The effect is greater on the small paintings. The net might be considered as a metaphor of a shade of oblivion drawn upon the pictures: the fading images of the near past which the artist seeks to forget through the act of depiction.

“Looking to the past with sorrow” is not a mourning for the past time, but it looks at the near past with sort of a contempt. It does not idealize the past but explores its absurdness. In Sudeh Davoud’s paintings the main subject matter are women –a common feature in Iranian contemporary art. In her previous exhibition in 2013 she casts a critical look to the Iranian young women, in her own words “being trapped in their safe encloses beating in the rhythm of idleness”. Here the young women are still depicted as victims of their self-constructed limits. But here the artist has more directly focused on her personal, immediate lived experience, making a combination of autobiographical issues with social critique. Her immediate encounter with near past memories point to the ephemeral nature of life and the evasive quality of the presence of people in our lives.

Faces are generally laughing. Davoud’s figures laugh as they fade, and recede as wrapped in an echo of laughter. Laughing is the privileged of man. As Umberto Eco maintains, “Man is the only laughing animal because, unlike other animals, we know we have to die. Laughter is a way to tame death, a way not to take our death too seriously, by not taking too seriously our life.” Hobbes claims that all laughter contains a sense of superiority, and Freud notes that there is some naughty content concealed beneath all jokes. These images of laughter, however, are not caused by something humorous. They are not an outburst of sentiments. They are, however, artificial smiles made for the camera. A harmless pulse we make, or we try to win us a more beautiful face. However, a constant laugh betrays a fool. Laughter, a sign of solidarity and sympathy, here takes a sinister, satirical tone.

Sude Davoud’s paintings are an invitation to a world of painterly touches and drips, freely and effortlessly making up figures, freezing them in a moment of their existence and float them in this colorful world. They bring us to a time when art was still intervowen with craftsmanship; when skill was taken for granted to make it easier to concentrate on the content. A world in which unprecedented incidents keep emerging out of artistic devices and preparations, making up the moment of the panting.

Golab Dare

Mixed media on canvas - 100 x 100 cm

Oil on paper - 50 x V0 cm

Oil on paper - 32 x 42 cm

Wednesday

Oil on paper - 100 x 70 cm

I Like Alooche

Oil on paper - 41 x 53 cm

Last Supper

Oil on paper - 41 x 53 cm

Oil on paper - 36 x 46 cm

Oil on paper - 100 x 70 cm

View The Face of Milad Tower

Mixed media on canvas - 130 x 150 cm

Oil on paper - 100 x 70 cm

Oil on paper - 38 x 56 cm